The map of poverty was manufactured

Seven decades of aid. Trillions of dollars.

In 1913, a shadowy American diplomat named Colonel Edward House sat down with the German Ambassador to the United States and floated an idea that would not be taken seriously for another three decades. What if the world’s powerful nations coordinated to develop “the waste places” of the globe? What if they brought progress to the poor?

House was ahead of his time. His proposal anticipated what we now call International Development—the post-World War II project of wealthy nations transferring resources, expertise, and capital to lift poor countries out of poverty.

Seven decades later, we can deliver a verdict on that experiment.

It failed.

Not in the way most critics imagine. Not because donors were too stingy or recipient governments too corrupt. It failed because the entire premise was flawed from the start—built on a misreading of how global poverty was created in the first place.

Andrew Brooks, a geographer at King’s College London, makes this case in his book “The End of Development.” His argument cuts against nearly everything we assume about why some nations prosper while others languish. And it starts with a question that seems almost too obvious to ask.

Why is Africa poor?

The intuitive answer involves geography. Harsh climates. Poor soils. Rugged terrain. Tropical diseases. It feels right. Look at the Sahara Desert—dry, desolate, impoverished. Look at the Swiss Alps—mountainous, yet affluent. Geography must matter.

Except it doesn’t hold up.

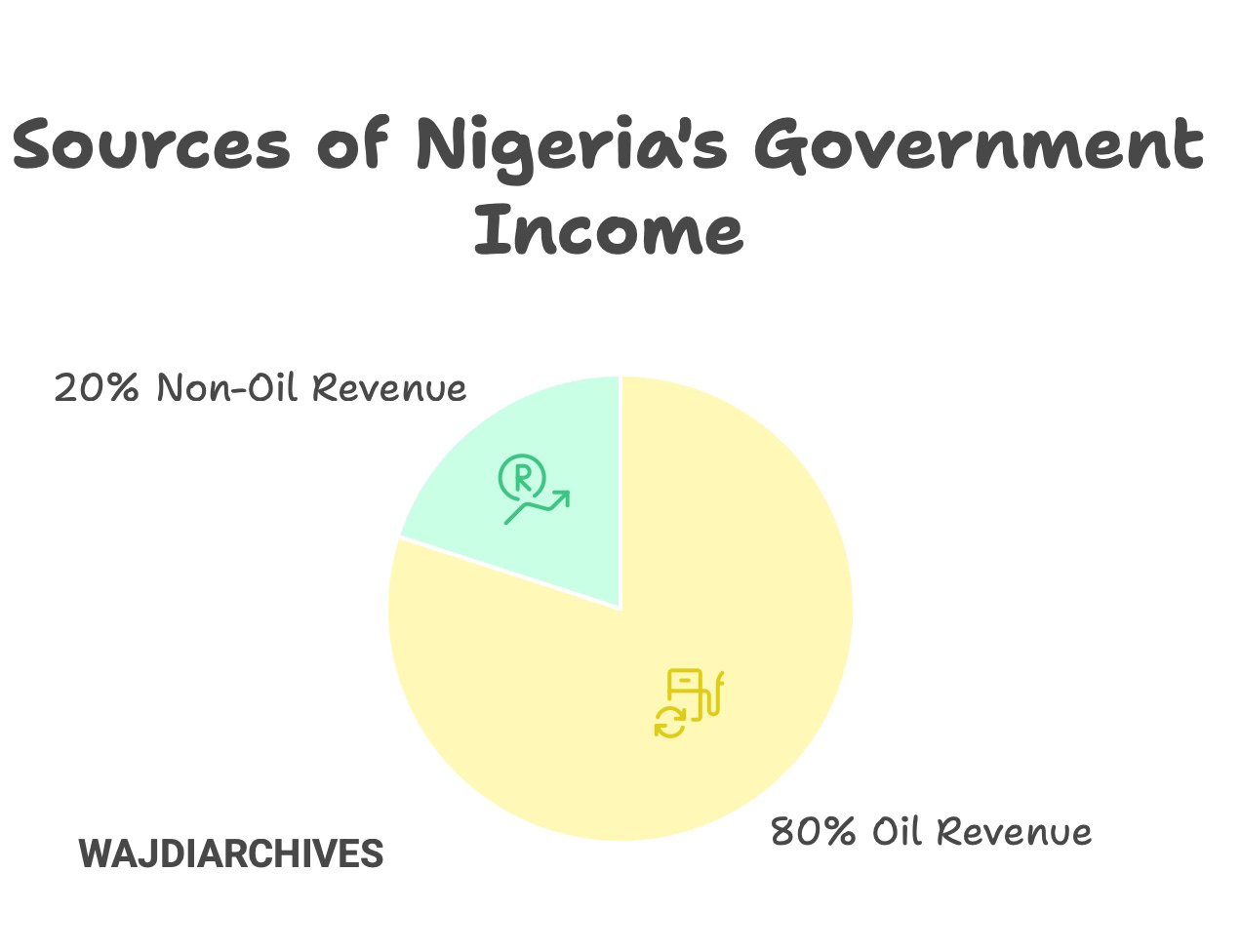

Saudi Arabia is equally dry and desolate. Nigeria sits on more oil than Switzerland has mountains. The rainforests of Queensland are humid and tropical, yet Australians enjoy some of the highest living standards on earth. The Democratic Republic of Congo has rainforests too. It has some of the world’s most desperate poverty.

As Brooks documents, environmental determinism—the idea that nature controls human destiny—is “a popular, intuitive and elegantly simple explanation for inequalities, but one that is almost entirely wrong.”

The evidence goes deeper than cherry-picked examples. Archaeological and historical research shows that before European colonization, sophisticated civilizations flourished across Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The feudal states of medieval West Africa—along the Limpopo River, in Great Zimbabwe, throughout the Upper Guinea Coast—were comparable in political complexity to medieval Europe. Chinese navigators sailed ships of 3,000 tons when Columbus’s Santa Maria displaced barely 100. The Great Wall was constructed centuries before Christ was born.

Europe did not have a head start. It had no natural advantage. What it had was something else entirely.

The year 1492 marks a hinge point in human history, though not for the reasons we typically celebrate.

When Columbus crossed the Atlantic, he initiated what historians call the Columbian Exchange—the transfer of plants, animals, and diseases between the Old and New Worlds. The ecological consequences were staggering. American crops like potatoes, tomatoes, and maize transformed European diets. Old World livestock reshaped American landscapes.

But the most consequential exchange was invisible.

European germs—smallpox, measles, typhus, plague—swept through indigenous populations that had no immunity. In central Mexico alone, the population collapsed from around 15 million to 1.5 million within 150 years. As Brooks notes, far more people died from disease than from Spanish swords.

This biological catastrophe created an opportunity for extraction on an unprecedented scale. The conquistadors didn’t just find gold in the Americas. They found labor shortages in lands suddenly emptied of workers. The solution was the Atlantic slave trade.

What followed was a global restructuring of economic geography. Latin American gold and silver flowed to Seville, then to Amsterdam and London, providing the capital that financed early industrial capitalism. Enslaved Africans produced the cotton that fed the textile mills of Lancashire. As Brooks writes, “capital from the slave trade helped to bank roll the Industrial Revolution and enriched Britain.”

The patterns we see on today’s wealth map—the familiar division between “developed” and “developing” nations—were not determined by climate or geography. They were manufactured through five centuries of extraction, exploitation, and the strategic application of violence.

This history matters because it exposes the contradiction at the heart of International Development.

After World War II, the newly independent nations of Africa and Asia were told they could achieve prosperity by following the Western model. Modernize your economies. Open your markets. Accept foreign investment. The money would flow in, the benefits would trickle down, and eventually you would join the club of developed nations.

The theory had a name: modernization. Its apostles included American academics who believed that all societies progressed through predictable stages toward an endpoint that looked remarkably like mid-century America. As the economist W.W. Rostow put it, traditional societies would “take off” into sustained growth if they adopted the right policies.

The theory also had a convenient alignment with Cold War strategy. Western development assistance promised newly independent nations a path to prosperity that didn’t require Soviet revolution. It was capitalism as liberation.

Here is where the story turns dark.

By the 1970s, many African and Latin American governments had borrowed heavily from Western banks. When interest rates spiked in the early 1980s, they couldn’t repay. The debt crisis that followed gave Western institutions—particularly the IMF and World Bank—enormous leverage over the economic policies of indebted nations.

The result was structural adjustment. In exchange for debt relief, poor countries were required to slash government spending, privatize state enterprises, remove trade barriers, and open their economies to foreign investment. The theory was that free markets would allocate resources efficiently and spark growth.

The practice was different.

As Brooks documents, structural adjustment “deindustrialized” Africa. Local manufacturing collapsed under competition from cheap imports. Governments gutted public services. Inequality widened. The 1980s became known as “the lost decade of development.”

Here is the punch line that isn’t funny at all: structural adjustment worked exactly as intended. Not as a poverty-reduction strategy, but as an expansion of global capitalism. It “opened up new territory to flows of capital by enforcing economic liberalization.”

International Development was never really about helping poor people. It was about extending the market.

The question of why some nations prospered while others remained poor has a simple answer, once you strip away the ideological fog.

Control.

The countries that escaped poverty—South Korea, China, and earlier Japan—did so by controlling their own capitalist development. They protected domestic industries. They regulated foreign investment. They prioritized education and infrastructure before liberalization. As Brooks observes, “both nations protected their domestic markets and had control over their own capitalist development.”

The countries that stayed poor were those denied this control—first by colonialism, then by debt, then by the structural adjustment programs that dictated economic policy from Washington.

A Chinese envoy to Malawi reportedly told local journalists: “No country in the world can develop itself through foreign aid. That is a fact. To develop your economy is your job, you have to do it yourself.”

The diplomat understood something that Western development experts still struggle to accept: the nations that succeeded did so by ignoring Western advice.

Today, the old paradigm is collapsing.

China’s engagement in Africa operates by different rules than traditional Western aid. The BRICS nations are reshaping global economic architecture. Local elites in African capitals navigate between competing powers, extracting benefits through what scholars call “extraversion”—using their position as gatekeepers to foreign markets.

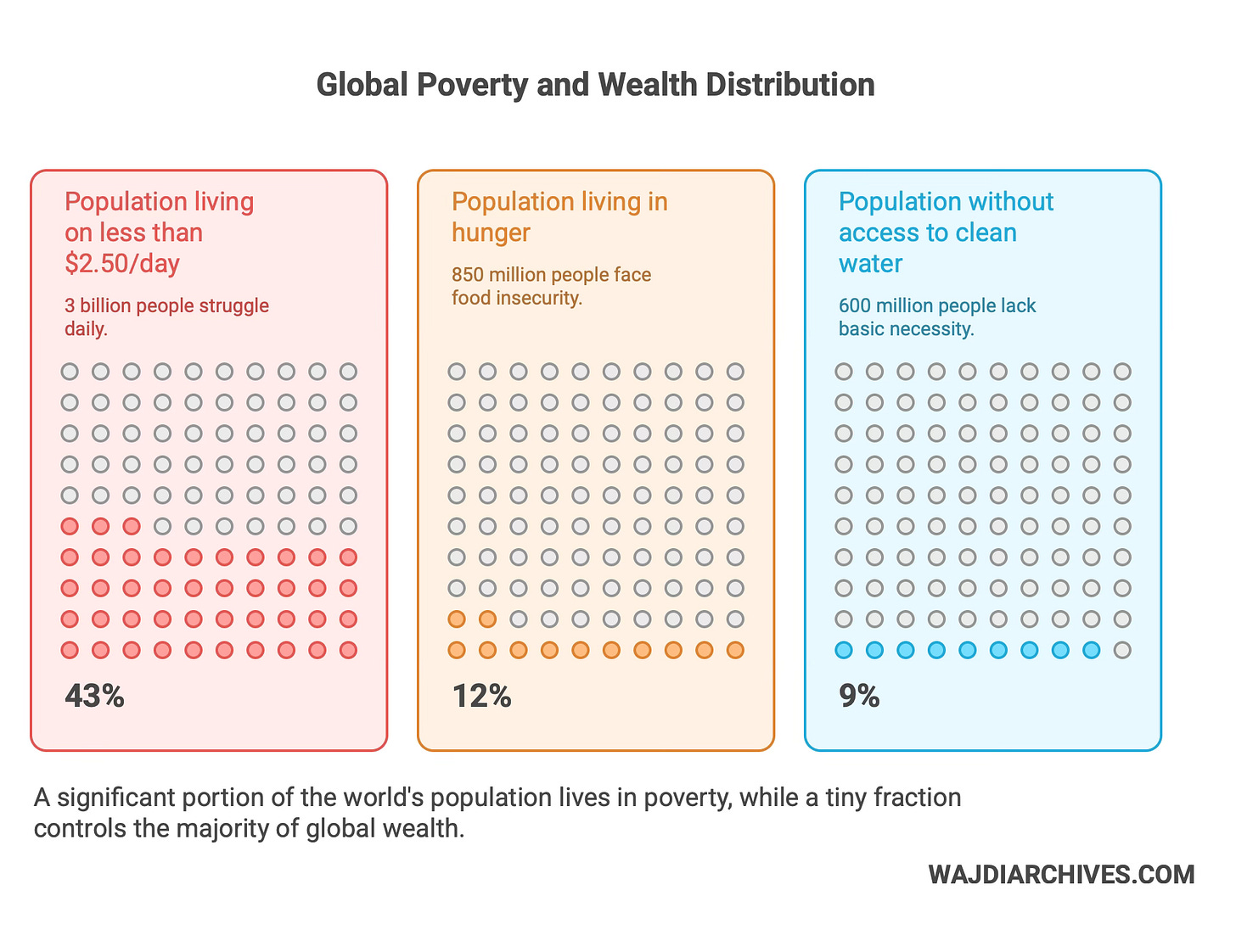

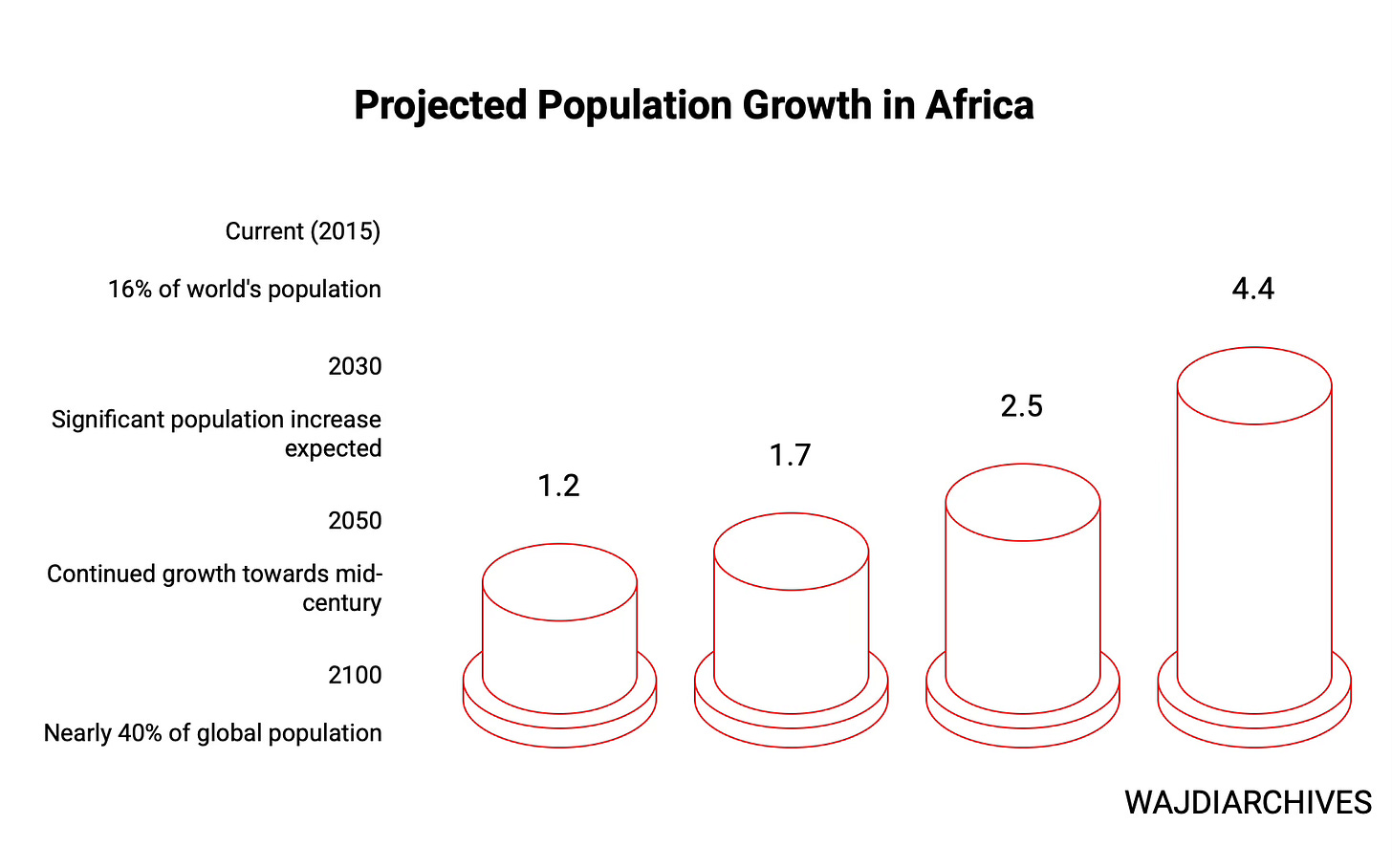

Meanwhile, the statistics tell a story that contradicts the narrative of progress. Africa loses $58 billion more each year than it receives in loans, grants, and investment—drained through corporate profits, tax avoidance, and the costs of climate change mitigation. The richest 62 people on earth now own as much as the poorest half of humanity. Inequality hasn’t narrowed. It has exploded.

Brooks calls this “the end of development”—not the end of capitalist expansion, but the exhaustion of the Western-led project that claimed to be something nobler. The donors and development banks still operate, but their ability to shape outcomes is diminishing, and their track record offers little reason for the poor to listen.

What comes next is harder to envision than what came before.

The policy prescription that emerges from this analysis is unglamorous: regulate the market, curtail borrowing, protect domestic industries, and avoid another lost decade. It is not a revolutionary program. It does not promise transformation. It merely suggests that poor countries should have the same freedom to manage their own economic development that today’s rich countries once enjoyed.

Whether they will have that freedom is another question.

The 62 billionaires who own half the world’s wealth are not going away. Neither are the multinational corporations extracting Africa’s resources, or the international institutions that still condition assistance on market-friendly reforms. The game has not ended. The rules have simply become more transparent.

Brooks concludes that capitalism “reproduces inequality”—not as a malfunction, but as a feature. To address global poverty means confronting this reality rather than imagining that better-designed aid programs or more innovative financial instruments will somehow produce different results.

This is not an optimistic conclusion. But it has the advantage of being true. And understanding why things are the way they are is the prerequisite for changing them.

Colonel House’s vision of powerful nations coordinating to develop “the waste places” of the world was not simply premature. It was premised on a misunderstanding of how those places came to be considered waste in the first place. Seven decades of International Development later, we are still living with the consequences of that error.

The question is what we do now.

Sources

Brooks, Andrew. “The End of Development: A Global History of Poverty and Prosperity.” London: Zed Books, 2017.

Seymour, Charles. “The Intimate Papers of Colonel House: Behind the Political Curtain 1912–1915.” Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1926.

Blaut, J.M. “Eight Eurocentric Historians.” New York: Guilford Press, 2000.

Blaut, J.M. “The Colonizer’s Model of the World.” New York: Guilford Press, 1993.

Drake, N.A. et al. “Ancient watercourses and biogeography of the Sahara explain the peopling of the desert.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011.

Arrighi, Giovanni. “The Long Twentieth Century.” London and New York: Verso, 1994.

Hart, Gillian. “D/developments after the meltdown.” Antipode, 2010.

Harvey, David. “The New Imperialism.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Smith, Neil. “Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space.” Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008.

Gilroy, Paul. “The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness.” London: Verso, 1993.

Escobar, Arturo. “Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World.” Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Jerven, Morten. “Africa: Why Economists Get It Wrong.” London: Zed Books, 2015.