Here's a question most Americans get wrong

on immigration

Here’s a question most Americans get wrong.

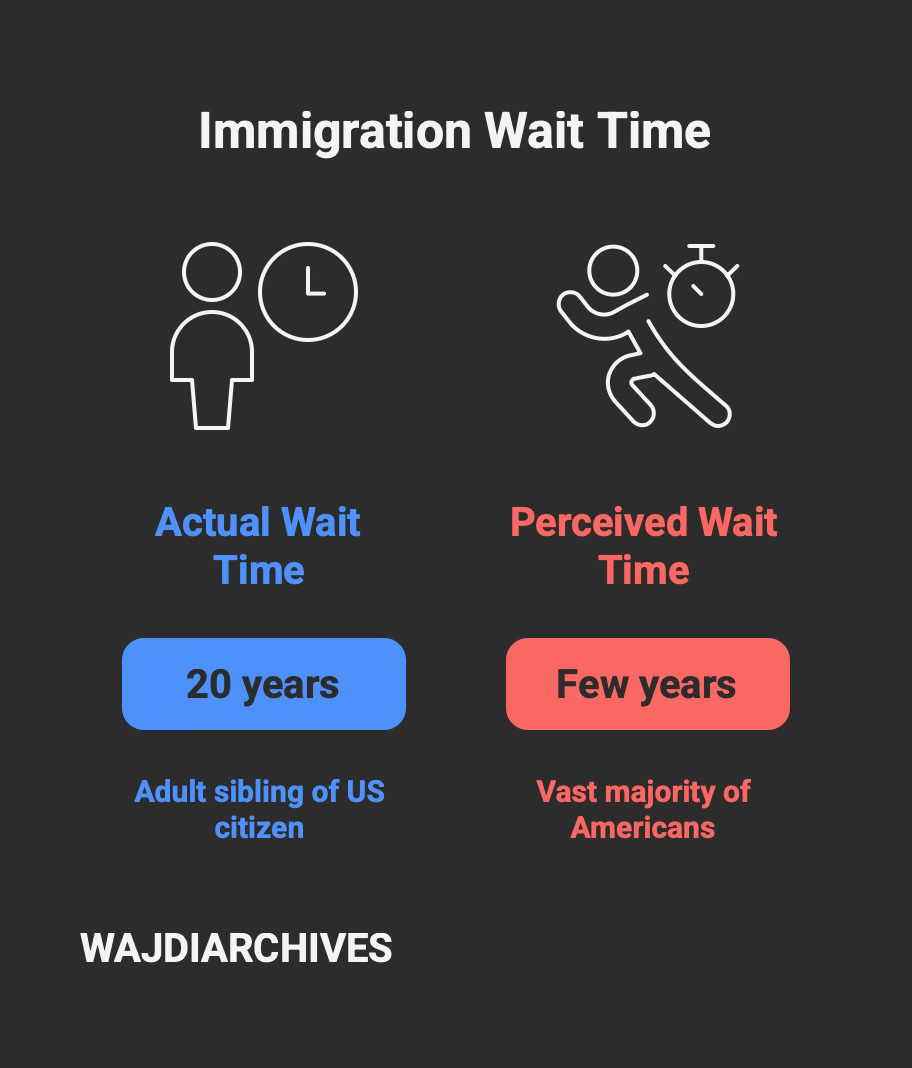

How long does it take for the adult sibling of a US citizen, living in Mexico, to legally immigrate to the United States?

A few months? A year? Maybe two or three years?

According to a YouGov poll cited by Taylor Orth, only 1% of respondents gave the correct answer: approximately 20 years.

That’s not a typo. Two decades of waiting, paperwork, uncertainty. For someone who already has a sibling who’s a citizen.

The striking part? When asked how long it should take, the vast majority of Americans—including Republicans—said a few years at most.

There’s a gap here. A massive one. And a new study suggests this gap might be the key to something researchers have been struggling with for years: actually changing people’s minds about immigration.

Alexander Kustov at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and Michelangelo Landgrave at the University of Colorado Boulder ran an experiment that challenges a lot of conventional thinking.

For years, researchers have tried to shift public opinion on immigration by correcting misperceptions. Americans overestimate how many immigrants there are. They overestimate immigrant crime rates, as Light, He, and Robey documented in their 2020 analysis of Texas data. They exaggerate cultural differences, as Flores and Azar showed in 2023.

The logic seems obvious: give people the correct facts, and they’ll update their views.

It hasn’t worked.

Study after study has found that even when you successfully correct these factual errors, policy preferences barely budge. Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin found this in 2019. Kustov, Laaker, and Reller confirmed it in 2021. The pattern is consistent enough that it’s become something of a puzzle in political science.

Why would beliefs change but preferences stay frozen?

Michael Tesler proposed an answer back in 2015. Some beliefs are “crystallized”—they’re woven into people’s broader worldviews, their partisan identities, their moral frameworks. You can technically update the factual belief, but the underlying attitude has roots that go deeper than any one data point.

Kustov and Landgrave had a different idea.

What if the problem isn’t that information doesn’t work? What if the problem is that researchers have been providing the wrong information?

Most Americans know almost nothing about how the immigration system actually functions.

That might sound like an exaggeration. It isn’t.

In the nationally representative survey Kustov and Landgrave conducted, they asked respondents to estimate wait times for different categories of potential immigrants. A doctor without a job offer. A famous athlete. A nanny with a job offer. An adult sibling of a citizen. An aunt or uncle of a citizen.

The average correct response rate was 25%. Random guessing would get you 20%.

Here’s the detail that stuck with me: only 8% of respondents correctly answered that aunts and uncles of US citizens are not eligible for family-based immigration at all. The question wasn’t about timing. It was about whether the path even exists.

92% of Americans thought there was a legal pathway that simply doesn’t exist.

This ignorance wasn’t concentrated in any particular group. The researchers tested for differences across age, race, education, income, party identification, and ideology. The gaps were negligible. College-educated liberals were slightly more knowledgeable—by a few percentage points. Practically speaking, everyone was equally uninformed.

As the Cato Institute’s Emily Ekins and David Kemp noted in their 2021 survey, Americans tend to assume their immigration system is much more straightforward and open than it actually is.

David Bier at Cato has documented just how byzantine the system really is. Nearly two hundred different visa categories. Application fees and legal costs running into thousands of dollars. Average wait times for visa appointments of 244 days—and that’s before the actual processing begins. Country-specific caps that mean immigrants from places like India, China, Mexico, and the Philippines can wait decades for green cards they’re otherwise fully qualified to receive.

The US immigration system is, in the language of public administration scholars like Donald Moynihan, Julie Gerzina, and Pamela Herd, administratively burdensome in ways most citizens never encounter and therefore never imagine.

So Kustov and Landgrave designed an experiment around this blind spot.

They recruited a nationally representative sample of 1,000 Americans through YouGov in May and June of 2023. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of three conditions.

One group read a neutral paragraph defining basic migration terminology. This was the placebo.

A second group read about administrative burdens: the hundreds of visa categories, the thousands of dollars in fees, the years of waiting.

A third group read about restrictions: the annual caps, the country-specific quotas, the reality that some eligible applicants wait decades.

Both treatment texts were about 150 words. Factual, verifiable, non-judgmental. No emotional appeals, no stories about specific immigrants, no arguments about whether immigration is good or bad.

Just information about how the system works.

The results were clear.

After reading about administrative burdens or restrictions, respondents were significantly more likely to believe immigration is difficult. That might seem obvious—you told them it was difficult, and they believed you. But the manipulation check matters because it confirms the information actually landed.

More importantly, respondents also shifted their policy preferences. About 13 percentage points more respondents—a 35% increase over baseline—reported supporting more open legal immigration or wanting to make the process easier.

The effect size was consistent across both treatment conditions. It held up after controlling for pre-treatment covariates. And in exploratory analysis, the researchers found positive effects across most political and demographic subgroups, including both Democrats and Republicans.

This wasn’t just Democrats becoming more liberal. The information moved people across the spectrum.

A natural question: maybe this was a fluke?

Kustov and Landgrave anticipated that. They’d run a pilot study seven months earlier using a different sample—912 respondents from Prolific, which tends to skew younger and more liberal than the general population.

The pilot used slightly different materials, including a political cartoon showing a figure lost in an “immigration maze.” Despite these variations, the results were nearly identical. Respondents who received information about immigration difficulty became more likely to believe immigration was difficult and more likely to support increasing immigration levels.

The effect replicated.

There’s a theoretical reason to expect this approach to work better than traditional fact-checking.

Alexander Coppock, in his 2023 book on political persuasion, draws a distinction between interventions that make existing knowledge “accessible” versus those that make new knowledge “applicable.”

Most immigration information experiments do the former. They remind people of facts they’ve probably encountered before—crime statistics, demographic projections, economic impacts. These facts are already floating around in public discourse. People have had opportunities to integrate them into their worldviews or reject them.

Information about the immigration process is different. Most people have never encountered it. They’ve never had reason to think about green card waiting times or country-specific caps. Their beliefs aren’t crystallized because they barely exist.

When you provide genuinely novel information, people don’t have pre-built defenses. The information can actually land.

The researchers are careful about what they’re claiming and what they’re not.

They don’t know if the effects persist over time. Immigration attitudes are generally stable in the long run, as Kustov, Laaker, and Reller documented in 2021. A short-term shift in a survey might not translate into durable opinion change or voting behavior.

They also don’t know the mechanism. Maybe people feel empathy for immigrants facing bureaucratic obstacles, as Scott Williamson and colleagues suggested in their 2021 work on family immigration histories. Maybe people perceive systemic injustice and want to align the system with American values of fairness, as Morris Levy and Matthew Wright argued in their 2020 book. Maybe people just see inefficiency and want it fixed.

The study wasn’t designed to distinguish between these possibilities.

And the sample size wasn’t large enough to detect small differences between the two treatment conditions or to identify which specific subgroups were most responsive.

But here’s what strikes me as the core finding.

For years, advocates for more open immigration have tried to persuade skeptics by arguing that immigration is good. Immigrants commit less crime. Immigrants start businesses. Immigrants contribute more in taxes than they receive in benefits.

These arguments are often true. They’re also often ineffective, precisely because they engage with beliefs people already hold strongly.

Kustov and Landgrave suggest a different framing. Instead of arguing that immigration is good, explain that immigration is hard.

Not “hard” in the sense of being a difficult policy problem. Hard in the sense that the people trying to navigate it face genuine obstacles. Hard in the sense that the system itself is more restrictive and burdensome than most Americans realize.

This reframe doesn’t require anyone to abandon their existing values. It doesn’t ask immigration skeptics to suddenly embrace open borders. It just provides context most people lack.

And apparently, that context matters.

There’s one more detail worth noting.

When asked how long various categories of immigrants should have to wait, Americans consistently gave answers much shorter than the actual wait times. This was true across party lines.

People aren’t opposed to legal immigration in the abstract. They’re operating with a mental model of the system that bears little resemblance to reality.

The gap between what Americans think the immigration system is and what it actually is might be one of the most consequential information asymmetries in contemporary politics.

Kustov and Landgrave have shown that closing that gap—even partially, even briefly—can move public opinion in a direction that years of traditional fact-checking efforts have failed to achieve.

Whether advocates, policymakers, or anyone else will act on that finding is a different question.

But now you know something most people don’t.

The next time someone tells you immigrants should “just come legally,” you’ll understand why that phrase carries more weight than it might seem.

Sources

Kustov, Alexander, and Michelangelo Landgrave. “Immigration is difficult?! Informing voters about immigration policy fosters pro-immigration views.” Journal of Experimental Political Science (2025): 1-13.

Bier, David J. “Why Legal Immigration is Nearly Impossible: U.S. Legal Immigration Rules Explained.” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 950 (2023).

Coppock, Alexander. Persuasion in Parallel: How Information Changes Minds about Politics. University of Chicago Press (2023).

Ekins, Emily, and David Kemp. “E Pluribus Unum: Findings from the Cato Institute 2021 Immigration and Identity National Survey.” Cato Institute (2021).

Hopkins, Daniel J., John Sides, and Jack Citrin. “The Muted Consequences of Correct Information about Immigration.” The Journal of Politics 81, no. 1 (2019): 315-20.

Kustov, Alexander, Dillon Laaker, and Cassidy Reller. “The Stability of Immigration Attitudes: Evidence and Implications.” The Journal of Politics 83, no. 4 (2021): 1478-94.

Light, Michael T., Jingying He, and Jason P. Robey. “Comparing Crime Rates between Undocumented Immigrants, Legal Immigrants, and Native-Born US Citizens in Texas.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, no. 51 (2020): 32340-7.

Orth, Taylor. “Support for Immigration is Much Higher among Young Americans than Old Ones.” YouGov (2022).

Tesler, Michael. “Priming Predispositions and Changing Policy Positions: An Account of When Mass Opinion is Primed or Changed.” American Journal of Political Science 59, no. 4 (2015): 806-24.